My answer was: It depends... I know, I know, it's not a very satisfying answer!

However, the concept of refactoring is quite broad, so it's hard to group everything under a single answer. Let's take a moment today to talk about the different types of refactoring, why they are relevant, and, most importantly, when they are relevant.

Code Readability and Clarity

A first type of refactoring aims to increase the readability and clarity of the code. We want the latter to be as easy to understand as possible. A developer spends the vast majority of their time reading rather than writing. The ratio is around 90% reading time, versus 10% writing time. It is therefore relevant to work on increasing reading speed when a team wants to increase its development speed.

When is it Relevant to Work on Code Readability? Always!

During the development of a feature, it is essential to structure the code well, name variables and functions effectively, and ensure files are well-formatted. The earlier the effort is made, the better the development will go and the less significant subsequent refactoring will be.

When our feature requires modifying existing code, it often means the code has lacked a little love. The refactor then becomes relevant to clarify what the code does, develop the necessary knowledge to perform the work, and simplify the code for those who will pass by later.

Recommendation: When a refactor could facilitate your work, create a branch next to the features with only the refactoring. Open a "merge request" with these changes and start your feature on these changes. Separating the refactor and the feature will make your peers' work easier when reviewing your code.

New Software Architecture

When I was discussing with Rafaël, he told me stories about developers who mentioned large refactors requiring several days of work. This type of change is rarely only to increase readability. Generally, it occurs when the current architecture no longer meets the new needs of the product. A new feature? A rapid change in product vision? There are several reasons.

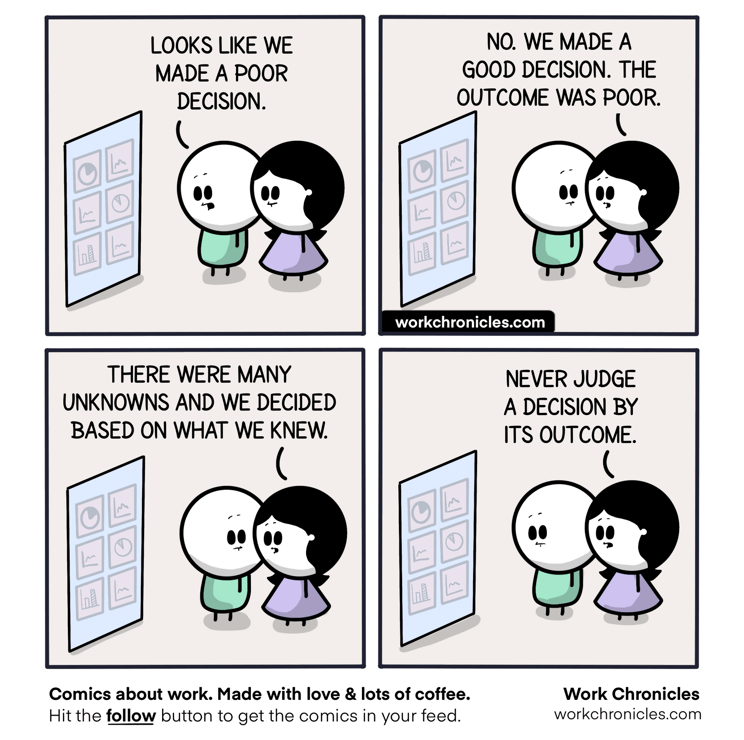

It is important to understand that the need to change the architecture does not stem from a bad decision or implementation. Keep in mind that the team that set up the initial architecture did so to the best of their technical knowledge, considering the product to be realized. We build software. As the name suggests, it's soft and flexible. We should expect the code to be malleable and constantly evolving.

Too often, this reality of software development is not explained to clients. Developing an application is extremely different from building a bridge. Building a bridge is complicated, but there are no unknowns. The plan is final and will be implemented in the same way, regardless of how many times it is built. It is not possible to say during construction: "Hey, I changed my mind. I would like to have one more lane in each direction!". If building a bridge is complicated, developing an application is something complex. For the same feature, there are a thousand ways to implement it. Moreover, it is possible, and even common, for the client to make changes along the way!

Therefore, it is necessary to explain to clients and managers that changes in the existing code do not necessarily indicate that the work was initially poorly done.

The Scouts' Rule for Refactoring

During the development of a product, team conventions can change. Whether it's for naming, file structuring, or communication between two systems, there will always be changes in the way things are done. When this happens, care must be taken in how these changes are applied. Applying a decision to the entire project can have major repercussions. Depending on the size of the latter, a convention change may require several days of work before the entire project is up to date. It is in these situations that management and even the client begin to ask questions. This kind of refactor is extremely difficult to explain and justify. How can we prevent this from happening?

An interesting practice is one of the Scout rules: always leave the place a little cleaner than when we arrived. This means a refactor should be applied only in the part of the code on which the team is working.

Take, for example, a team that decides to abstract a library to eventually eliminate it. The first reflex would be to do the work all at once! However, this is used everywhere in the application, so it represents a colossal change. A whole week of work. What will happen, in the short term, to the team's velocity if the change is made all at once? It will decrease! And that's when the client starts asking questions.

And what if, in addition to the decrease in velocity, an error is introduced into a part of the application that has not been in development for months? What will happen? More questions from the client!

Making the change all at once has a significant impact on product development, as you can see. Using the scout rule and applying the change only if necessary in this part of the code solves these problems. As development progresses, our library abstraction will continue to advance. It can take 6 months, 1 year, or 2 years! The goal is to constantly increase the quality of the code without causing adverse impact. By applying this rule, it becomes unnecessary to justify this type of work to the client.

How to Change Your Vocabulary to Better Promote Refactoring

The term "refactor" doesn't mean much to those who are not in our field. It can even scare some people! All it takes is one bad experience with a development team, and the word becomes a "red flag" for the client. A change in the developers' speech can greatly improve communication with the product team and the client. It's about replacing the word "refactor" in our vocabulary with "preparing the ground".

Before starting a feature, we need to examine and analyze the code, and then prepare the ground to do our job well. This is an essential step in software development to ensure a quality product that evolves well over time. This is part of our job as software developers, and we should not have to justify it, just as an electrician should not have to justify the time it takes to cut the power before doing their job.

Changing our vocabulary to say that we are preparing the ground leads us to ask interesting questions about the refactoring we want to carry out.

- Is it relevant to prepare the ground after completing a task?

- Is it relevant to prepare the ground for work to be done in three months?

- Is it necessary to prepare a ground the size of a football field for a feature as small as a shed?

This way of communicating brings a certain structure to the size, timing and relevance of a refactoring.

I would like to finish with a quote from Martin Fowler from his book Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code:

Software developers are professionals. Our job is to build effective software as rapidly as we can. My experience is that refactoring is a big aid to building software quickly. [...] A schedule-driven manager wants me to do things the fastest way I can; how I do it is my responsibility. I'm being paid for my expertise in programming new capabilities fast, and the fastest way is by refactoring—therefore, I refactor.

Got a tech project in mind?

Work with a team that maximizes and accelerates the impact of your software investments.

Continue reading

Predictability: 10 Years of Evolution in Agile Estimation